... of the Sphere

A blog aiming to give an insight into my thought and work processes, showcasing works in progress and (for the time being) reconciled, and logging explorations and experimentations. An additional communication tool to an image-based website. Website:www.rosemariepowellsculpture.co.uk

Monday, 24 December 2012

Thursday, 13 December 2012

Part IV - Painting

Some of the outcomes of an oil painting induction workshop I attended in the autumn:

- exploring marks and texture

- exploring marks and texture

- series using 3 elements of our choice (with a degree of 'creativity' in adhering to the rules), in this instance 1) Indian yellow with and without medium, 2) black oil stick, and 3) cadmium red diluted with oil to make dripping consistency

Tuesday, 11 December 2012

Part III - Plaster

What I have come to refer to as my plasterworks - exploring plaster as a material and playing with the numerous different stages of the curing process. Inspired by/based on 'bringing the spirit of the material to life, letting the material speak. Investigating the possibilities this opens up.

Fostering the revelation of anything arising spontaneously and not be bound by previously predominant forms' as per the '2012' page of my website:

Some of my favourites on that board:

- the very delicate - complete happenstance

- gravity and chance playing their part

creating intriguing cavities

Fostering the revelation of anything arising spontaneously and not be bound by previously predominant forms' as per the '2012' page of my website:

Some of my favourites on that board:

- the very delicate - complete happenstance

- gravity and chance playing their part

- a haphazard construction; the result of a series of (fairly gentle) forcible propulsions through the air

creating intriguing cavities

Monday, 10 December 2012

Part II - Space (b)

Further exploring 'incorporating space as a positive element'.

Large rudimentary maquette. This is a saddle plane, carved out towards its periphery, with the opposing edges brought together to maximize the curve:

Large rudimentary maquette. This is a saddle plane, carved out towards its periphery, with the opposing edges brought together to maximize the curve:

Sunday, 9 December 2012

Part II - Space

As per the '2012' page on my website, here is the second part (the posts on the Fragility Spheres constituted the first) of what is seemingly turning out to be the end-of-year survey of my explorations of the past months:

'incorporating space as a positive element ...'

Some of the maquettes that may lead to further exploration and development

'incorporating space as a positive element ...'

Some of the maquettes that may lead to further exploration and development

Ever Changing, Ever Unfinished - Nature's Chapter

This is a fragment of a very large sculpture I made in the summer (canine intervention - quite unintended and initially quite unwanted - left me with just this piece). I decided to put it in the garden and watch how it evolved exposed to the elements: the next chapter in the story of the plaster form and the plaster material - nature's hand in the process. All part of the overall creative process, offering a completely new and different beauty, inviting a new and different way of viewing and appreciation, going beyond the form and venturing closer into texture, colour differentiations, fractures, ... gravity and chance arranging the debris to work towards an 'installation' ...

Tuesday, 27 November 2012

Ever Changing so Ever Unfinished

Following on from the previous post related to Hilary Mantel and more specifically what she says about the book reverting to its unfinished state, a work in progress, in the sense that it is read and interpreted, and no two readers receive/interpret it in the same way; no two readers have the same experience.

Equally, in relation to visual art, no two viewers experience an artwork in the same way, so the artwork remains a work in progress in that same sense.

In my view, it also remains eternally unfinished in a second sense, i.e. when you consider and value the material you work with as an artist as an entity in its own right, a living thing with a story of its own - think of the story encapsulated in a marble carving: the millions of years of formation, the quarrying, the becoming a work of art, and very importantly the continuing to be.

Everything around us has a 'life', a story; everything is continuously changing, often so slowly that we think of it as constant.

Equally, in relation to visual art, no two viewers experience an artwork in the same way, so the artwork remains a work in progress in that same sense.

In my view, it also remains eternally unfinished in a second sense, i.e. when you consider and value the material you work with as an artist as an entity in its own right, a living thing with a story of its own - think of the story encapsulated in a marble carving: the millions of years of formation, the quarrying, the becoming a work of art, and very importantly the continuing to be.

Since what you make as an artist continues to live beyond your intervention (and the material 'lived'/had a life before you came into contact with it), you make a relatively brief appearance in the story of the material you are interacting with.

Everything around us has a 'life', a story; everything is continuously changing, often so slowly that we think of it as constant.

Thursday, 18 October 2012

Drawing a Parallel Between the Novelist's and the Sculptor's Work: the PERMANENT 'Unfinished' State

This is taken from the Dutch 'Boekvertalers' website:

www.boekvertalers.nl

The purpose of putting this article on literary translation on the Blog is to illustrate one of the fundamental principles in my work as a sculptor: my intervention as an artist on the material with which I create a 'piece' is only part - a small part - of the life of the piece/the material; it continues to live beyond my input.

(This article also brings together the two activities that have occupied my whole being during all of my professinal life: art and language/translation.

The part that is relevant to art is highlighted in red underscore. I'm including the other paragraphs because this is an illustration of a truly inspiring collaborative partnership, so rare in translation.

In this first section, replace 'book' by 'artwork', 'reader' by 'viewer', and in the final bit 'translator' by 'viewer'.

Again like many of my compatriots, I feel guilty for being so bad at languages, and guilty that I cannot help my translators more. Though usually, they have not asked. Queries have been restricted to a few difficult phrases, idiomatic or obscure. And I have often wondered what is the effect of my work in translation, since often there is no feedback after publication. I know I am a quirky writer, and make use of non-standard English and of different registers and tone; also, my writing is interrupted, or inflected — however you like to put it—by nods and winks to other writers, by quotations not marked by quotation marks, by allusions that probably only a few readers will grasp. I am not a difficult or obscure writer (I hope) but I am ferociously intertextual. Mostly, the sense of the passage remains intact for the reader, whether or not the teasing echoes are picked up. But I suppose some of my translators must think I am a very strange woman.

Too difficult to translate?

Wolf Hall, my 2009 novel, has been published in some 30 countries. Until then my translation record was patchy. A particular book would be picked up in one country, but not in another, and I never quite knew why that was: was it the state of the market, or was it that a particular novel seemed too difficult to translate? My publishers changed frequently, and I had no chance to build up a relationship with a translator. Contact would come only when the work was done, and the translator was tidying up after herself. The tone had been settled, the project was almost finished, and what remained for me to do was purely mechanical: it was the equivalent of putting the papers in a neat pile and fixing them together with a paperclip. Only recently, working with Ine Willems on the translations of Wolf Hall and Bring up the Bodies, I have realised that there is another, better way. It is possible for two minds to meet, and treat the translation as a new work. The novel then reverts to its unformed, unfinished state, as work in progress.

This seems to me a much better way, though it makes greater demands on both the translator and the original writer. I cannot consider a book finished when it leaves my hand. It must be read, translated, interpreted, and no two readers, even two readers who share a language, have the same experience. A great deal of the power of a book lies anterior to words, and beyond words. The power lies in the images that the word creates, each image unique to one reader and each image shifting, fluid, endlessly renewable. But still, I depend on the translator for the words that will spring that image. In the ideal world, the translator must be more than linguistically skilled, well-informed, well-read. She or he must also be intuitive, and able to align her intuition with that of the writer.

And of course, as an artist one mustn't forget that the viewer's intuition is coloured by his/her cultural background - an interesting and important aspect for me to consider, given that I spent my 'formative years' in Belgium and England has now very much become my home:

The whole picture

Such paragons are rare (and I think I have found one, though Ine will not like me to boast about her.) Clearly the translator’s task is far greater than that of finding word-by-word, line-by-line equivalents. It is about finding a tone that allows the writer’s personality to shine through the lines. But it is even more than that. We are not just translating a book, we are translating one culture to another. Given that there is generally a high level of technical competence among translators, this is where the challenges lie. The translator must stand back and consider the whole picture. A writer’s native audience has certain underlying assumptions about the world, and these assumptions shape a text, almost invisibly; but they are not necessarily shared by foreign readers. The author may not be aware of her own shaping assumptions, until a translator draws her attention to them.

For instance, my novel A Place of Greater Safety, though written in English, is about the French Revolution. It is now being translated into Dutch. So the question arises, what do the three nations know about each other? Ine has already told me that the Dutch will understand more about the administrative structure of pre-revolutionary France than the English do. Therefore, when describing the job held by the father of one of my revolutionaries, she can be more accurate and precise in Dutch than I could in the English original. That is welcome. But there is a further point, a more subtle one. The English, invariably, think local administrators are funny. They don’t have to say or do anything to amuse; they are just ridiculous by virtue of their position. So, for example, in an American city, a mayor is a person of consequence and is taken very seriously. But to the English, a major is likely to be a pompous individual strutting around in a medieval costume. (Modern mayors don’t do this, but they did until very recently, and it is unlikely we will ever let them forget it.) Now the questions arises, what do the Dutch think? Will they understand why my text, when I discuss town government, takes on a tone of mockery? Are local bureaucrats seen in the same way, all over the world? I don’t know. But I trust Ine to be aware of the issue, and think it through.

An exercise in magic

I feel enlightened by the discussions we have held, even though we have only been looking at the first dozen pages of the book. It is as if my unconscious assumptions are coming to light: as if the book’s resources are being mined. It feels deeper than any editing process I have ever undertaken, and much more revealing.

Let me return to my young self, struggling to learn French. At fifteen I decided that I would read Madame Bovary in French, just by myself. I did not get much further than one chapter; after that, I read with an English version at hand. If this was cheating, it was still productive; but I don’t remember much about that, I only remember my work on the early pages. It was a frustrating process but also brought me the deep reward that comes from struggling with something just beyond one’s competence: not so far beyond that one feels hopeless, but not a safe process, not a restful one. I remember that I was completely absorbed, and, as one says, ‘translated’ to another time and place. My struggles with the first chapter, my intense and deep striving, stays with me to this day, so that when I reread that part of the book, in English, it seems to me that it is hyper-real; as if the rest of the book is monochrome, but this chapter is in vivid colour. I will never be a linguist, but I am glad I made that effort, because it gave me, in a humble way, an insight into the process of translation. I understood that what I was trying to solve was a multi-dimensional puzzle, and I understood that the key did not lie within the French-English dictionary; it lay within the heart of Emma Bovary. I think most authors, if asked, would say, ‘Be faithful to the spirit of my book, not its letter.’ Conjuring that spirit is an exercise in magic, a magic more potent because most of its operations are hidden.

www.boekvertalers.nl

The purpose of putting this article on literary translation on the Blog is to illustrate one of the fundamental principles in my work as a sculptor: my intervention as an artist on the material with which I create a 'piece' is only part - a small part - of the life of the piece/the material; it continues to live beyond my input.

(This article also brings together the two activities that have occupied my whole being during all of my professinal life: art and language/translation.

The part that is relevant to art is highlighted in red underscore. I'm including the other paragraphs because this is an illustration of a truly inspiring collaborative partnership, so rare in translation.

In this first section, replace 'book' by 'artwork', 'reader' by 'viewer', and in the final bit 'translator' by 'viewer'.

In Writers’ Words: Hilary Mantel on translation

Like many Britons of my generation, I am virtually a monoglot. I was taught French at school but taught so badly that I had no confidence either in speaking or reading the language; essentially, it was taught to me as an extinct language, like Latin, and no acknowledgement was made of the fact that, within visible distance of our shoreline, millions of happy Frenchmen and women were chatting away.Again like many of my compatriots, I feel guilty for being so bad at languages, and guilty that I cannot help my translators more. Though usually, they have not asked. Queries have been restricted to a few difficult phrases, idiomatic or obscure. And I have often wondered what is the effect of my work in translation, since often there is no feedback after publication. I know I am a quirky writer, and make use of non-standard English and of different registers and tone; also, my writing is interrupted, or inflected — however you like to put it—by nods and winks to other writers, by quotations not marked by quotation marks, by allusions that probably only a few readers will grasp. I am not a difficult or obscure writer (I hope) but I am ferociously intertextual. Mostly, the sense of the passage remains intact for the reader, whether or not the teasing echoes are picked up. But I suppose some of my translators must think I am a very strange woman.

Too difficult to translate?

Wolf Hall, my 2009 novel, has been published in some 30 countries. Until then my translation record was patchy. A particular book would be picked up in one country, but not in another, and I never quite knew why that was: was it the state of the market, or was it that a particular novel seemed too difficult to translate? My publishers changed frequently, and I had no chance to build up a relationship with a translator. Contact would come only when the work was done, and the translator was tidying up after herself. The tone had been settled, the project was almost finished, and what remained for me to do was purely mechanical: it was the equivalent of putting the papers in a neat pile and fixing them together with a paperclip. Only recently, working with Ine Willems on the translations of Wolf Hall and Bring up the Bodies, I have realised that there is another, better way. It is possible for two minds to meet, and treat the translation as a new work. The novel then reverts to its unformed, unfinished state, as work in progress.

This seems to me a much better way, though it makes greater demands on both the translator and the original writer. I cannot consider a book finished when it leaves my hand. It must be read, translated, interpreted, and no two readers, even two readers who share a language, have the same experience. A great deal of the power of a book lies anterior to words, and beyond words. The power lies in the images that the word creates, each image unique to one reader and each image shifting, fluid, endlessly renewable. But still, I depend on the translator for the words that will spring that image. In the ideal world, the translator must be more than linguistically skilled, well-informed, well-read. She or he must also be intuitive, and able to align her intuition with that of the writer.

And of course, as an artist one mustn't forget that the viewer's intuition is coloured by his/her cultural background - an interesting and important aspect for me to consider, given that I spent my 'formative years' in Belgium and England has now very much become my home:

The whole picture

Such paragons are rare (and I think I have found one, though Ine will not like me to boast about her.) Clearly the translator’s task is far greater than that of finding word-by-word, line-by-line equivalents. It is about finding a tone that allows the writer’s personality to shine through the lines. But it is even more than that. We are not just translating a book, we are translating one culture to another. Given that there is generally a high level of technical competence among translators, this is where the challenges lie. The translator must stand back and consider the whole picture. A writer’s native audience has certain underlying assumptions about the world, and these assumptions shape a text, almost invisibly; but they are not necessarily shared by foreign readers. The author may not be aware of her own shaping assumptions, until a translator draws her attention to them.

For instance, my novel A Place of Greater Safety, though written in English, is about the French Revolution. It is now being translated into Dutch. So the question arises, what do the three nations know about each other? Ine has already told me that the Dutch will understand more about the administrative structure of pre-revolutionary France than the English do. Therefore, when describing the job held by the father of one of my revolutionaries, she can be more accurate and precise in Dutch than I could in the English original. That is welcome. But there is a further point, a more subtle one. The English, invariably, think local administrators are funny. They don’t have to say or do anything to amuse; they are just ridiculous by virtue of their position. So, for example, in an American city, a mayor is a person of consequence and is taken very seriously. But to the English, a major is likely to be a pompous individual strutting around in a medieval costume. (Modern mayors don’t do this, but they did until very recently, and it is unlikely we will ever let them forget it.) Now the questions arises, what do the Dutch think? Will they understand why my text, when I discuss town government, takes on a tone of mockery? Are local bureaucrats seen in the same way, all over the world? I don’t know. But I trust Ine to be aware of the issue, and think it through.

An exercise in magic

I feel enlightened by the discussions we have held, even though we have only been looking at the first dozen pages of the book. It is as if my unconscious assumptions are coming to light: as if the book’s resources are being mined. It feels deeper than any editing process I have ever undertaken, and much more revealing.

Let me return to my young self, struggling to learn French. At fifteen I decided that I would read Madame Bovary in French, just by myself. I did not get much further than one chapter; after that, I read with an English version at hand. If this was cheating, it was still productive; but I don’t remember much about that, I only remember my work on the early pages. It was a frustrating process but also brought me the deep reward that comes from struggling with something just beyond one’s competence: not so far beyond that one feels hopeless, but not a safe process, not a restful one. I remember that I was completely absorbed, and, as one says, ‘translated’ to another time and place. My struggles with the first chapter, my intense and deep striving, stays with me to this day, so that when I reread that part of the book, in English, it seems to me that it is hyper-real; as if the rest of the book is monochrome, but this chapter is in vivid colour. I will never be a linguist, but I am glad I made that effort, because it gave me, in a humble way, an insight into the process of translation. I understood that what I was trying to solve was a multi-dimensional puzzle, and I understood that the key did not lie within the French-English dictionary; it lay within the heart of Emma Bovary. I think most authors, if asked, would say, ‘Be faithful to the spirit of my book, not its letter.’ Conjuring that spirit is an exercise in magic, a magic more potent because most of its operations are hidden.

Art as a Commodity - Literally

This to me epitomizes the way the 'art market' has sucked the very soul out of Art and how the essence of Art is being lost completely:

This man has set up a website that sells shares in artworks, and interestingly towards the end of the video (2.01 minutes in) he reveals his true colours: asked whether his 'company' will be quoted on the stock market one day, he (proudly) says 'not yet but our success is growing ...'

This man has set up a website that sells shares in artworks, and interestingly towards the end of the video (2.01 minutes in) he reveals his true colours: asked whether his 'company' will be quoted on the stock market one day, he (proudly) says 'not yet but our success is growing ...'

Saturday, 6 October 2012

Food for Thought

A fascinating perspective given by Georges Bataille (to whom I referred in my post on Form & Formless), specifically related to literature, but very much applicable to Art.

Perhaps this offers a 'way in' to some of the art I have difficulty connecting with?

MUCH food for thought, in many different ways:

Perhaps this offers a 'way in' to some of the art I have difficulty connecting with?

MUCH food for thought, in many different ways:

Friday, 28 September 2012

A Closer Look at the 'Fragility' Spheres

My post of 17 August 2012 gave 'An Initial Glimpse' into the work I've been doing on the 'Fragility' spheres.

The first four spheres have test-fired well so I now feel the time is right to continue the process. I have grouped the four spheres together and the plan is to make several more and make an installation. All the spheres will be either white or black or a combination of the two. They will be of varying sizes.

My primary concern is to let the material and the process speak and for me to be simply there as an aid:

- making the process visible. I use the coiling technique which is a technique used in ceramics, but ceramicists tend to smooth out the coils; I want the process to remain visible. The spheres are made up of one continuous coil spiralling upwards - again, normally ceramicists use a process of cutting the coils to size and then placing one coil on top of another: cut to size, place, cut to size, place, and so on. I want this spiralling of one coil to remain visible too;

- inviting imperfections - cracks, uneven textures, small fractures, etc. - to reflect 'fragility', but more importantly to leave visible the way in which the type of clay I'm using behaves;

- the sphere, the spiral, expansion and contraction, growth and decay, all of which are universal.

Some images of the intitial four:

And some close-ups, highlighting the texture and cracks:

These spheres are originally inspired by my consciousness of the fragility of life. These thoughts coalesced with my discovering and enjoying the delicacy of this new clay I was using, a delicacy that infers fragility.

I initially intended to make this 'theme' a prominent element in the presentation of this piece (this is what I have tended to do in the past), but it occurred to me as I woke this morning that this would make the presence of me as the artist too manifest. The spheres must speak for themselves; the viewer must be allowed to/invited to connect with these spheres in their own individual way. So I shall keep the 'philosophizing' to myself (unless otherwise invited, of course!). Making these spheres is a deeply meditative process though, a process I very much enjoy, so the thinking is very much an integral part of the work.

My plans for exhibiting this piece are beginning to come together. I have always taken delight in the way objects/sculptures that are grouped together function very differently from one object/sculpture on its own. These - very quiet, peaceful - spheres speak so much louder when they're grouped together.

As I have said before, I intend to make a large installation with these and then show them in a way that sits more comfortably with how I feel art should be shown: the prime motive being not the usual commercial one but endeavouring to bring something new, a new exhibition experience to the viewer. I'm also examining the feasibility of the concept of not having these spheres for sale in the usual way, but inviting viewers to take one away as a memory of their experience of the show - the experience being what I want to stay with people rather than the buying of an object/a commodity. This would be one of the spheres that speaks to them most, with which they find a particular connection.

The idea that a connection is then created between these people, invisible, existing at a non-physical level. This could be taken further, with some of these people coming together after a year or so to share with each other the 'further life' of their sphere - how they, friends, family have enjoyed it, incidents around it, etc. - and they could bring friends and family who might also like to have one of the spheres. (This would mean I would have been making more in the meantime.) And so the connection continues to grow in depth and in scope, and another kind of sculpture would be beginning to be created, one that functions at a human/social level.

I also like the idea that the spheres themselves are building a life of their own, separate from me directly. This, of course, is the case with all art objects, indeed with all objects, with everything physical on the planet: nothing remains exactly as it is, everything is constantly evolving; we're just not always conscious of that fact.

The first four spheres have test-fired well so I now feel the time is right to continue the process. I have grouped the four spheres together and the plan is to make several more and make an installation. All the spheres will be either white or black or a combination of the two. They will be of varying sizes.

My primary concern is to let the material and the process speak and for me to be simply there as an aid:

- making the process visible. I use the coiling technique which is a technique used in ceramics, but ceramicists tend to smooth out the coils; I want the process to remain visible. The spheres are made up of one continuous coil spiralling upwards - again, normally ceramicists use a process of cutting the coils to size and then placing one coil on top of another: cut to size, place, cut to size, place, and so on. I want this spiralling of one coil to remain visible too;

- inviting imperfections - cracks, uneven textures, small fractures, etc. - to reflect 'fragility', but more importantly to leave visible the way in which the type of clay I'm using behaves;

- the sphere, the spiral, expansion and contraction, growth and decay, all of which are universal.

Some images of the intitial four:

And some close-ups, highlighting the texture and cracks:

These spheres are originally inspired by my consciousness of the fragility of life. These thoughts coalesced with my discovering and enjoying the delicacy of this new clay I was using, a delicacy that infers fragility.

I initially intended to make this 'theme' a prominent element in the presentation of this piece (this is what I have tended to do in the past), but it occurred to me as I woke this morning that this would make the presence of me as the artist too manifest. The spheres must speak for themselves; the viewer must be allowed to/invited to connect with these spheres in their own individual way. So I shall keep the 'philosophizing' to myself (unless otherwise invited, of course!). Making these spheres is a deeply meditative process though, a process I very much enjoy, so the thinking is very much an integral part of the work.

My plans for exhibiting this piece are beginning to come together. I have always taken delight in the way objects/sculptures that are grouped together function very differently from one object/sculpture on its own. These - very quiet, peaceful - spheres speak so much louder when they're grouped together.

As I have said before, I intend to make a large installation with these and then show them in a way that sits more comfortably with how I feel art should be shown: the prime motive being not the usual commercial one but endeavouring to bring something new, a new exhibition experience to the viewer. I'm also examining the feasibility of the concept of not having these spheres for sale in the usual way, but inviting viewers to take one away as a memory of their experience of the show - the experience being what I want to stay with people rather than the buying of an object/a commodity. This would be one of the spheres that speaks to them most, with which they find a particular connection.

The idea that a connection is then created between these people, invisible, existing at a non-physical level. This could be taken further, with some of these people coming together after a year or so to share with each other the 'further life' of their sphere - how they, friends, family have enjoyed it, incidents around it, etc. - and they could bring friends and family who might also like to have one of the spheres. (This would mean I would have been making more in the meantime.) And so the connection continues to grow in depth and in scope, and another kind of sculpture would be beginning to be created, one that functions at a human/social level.

I also like the idea that the spheres themselves are building a life of their own, separate from me directly. This, of course, is the case with all art objects, indeed with all objects, with everything physical on the planet: nothing remains exactly as it is, everything is constantly evolving; we're just not always conscious of that fact.

Labels:

Fragility Spheres

Monday, 24 September 2012

Form & Formless and Gutai

Following on from my previous post, some of the thoughts I have had over the past few months in relation to my enquiry into form - first addressed back in November 2011 - and for which my second encounter with 'These Associations' in the Turbine Hall last Saturday is proving to be something of a catalyst for imparting them now. I'm using images of some of the work I did in the Autumn of 2011 as the beginnings of my Gutai-inspired explorations, and I shall explain my work process and related thinking in the second part of this post:

- At what point in the creative process does a lump of clay become form (I have used 'a form' in the past, from the Germanic een vorm/ein Form), when does formless become form?

The French philosopher Georges Bataille spoke of l'informe

http://aphelis.net/georges-bataille-linforme-formless-1929/

and some further explorations of this concept provide a more concrete illustration

http://radicalart.info/informe/index.html

The list of words designating forms of formlessness includes nouns that appropriately define what is depicted in the first two/three images below - and perhaps, to some, in the last two images.

Formless?

Formless / form?

Form?

- At what point in the creative process does a lump of clay become form (I have used 'a form' in the past, from the Germanic een vorm/ein Form), when does formless become form?

The French philosopher Georges Bataille spoke of l'informe

http://aphelis.net/georges-bataille-linforme-formless-1929/

and some further explorations of this concept provide a more concrete illustration

http://radicalart.info/informe/index.html

The list of words designating forms of formlessness includes nouns that appropriately define what is depicted in the first two/three images below - and perhaps, to some, in the last two images.

Formless?

Formless / form?

Form?

Form is arising from formless as 'recognisable' structures/patterns emerge. And what are these 'recognisable' structures/patterns? I wonder - and I will expand on this further in a subsequent post - whether it has primordially to do with universal geometry (this hasn't quite fully jelled in my mind yet).

And now for an explanation of my work process for my initial Gutai-inspired work:

As I've said before, what inspired me about the Gutai approach was (and very much/increasingly continues to be) the idea of investigating the possibilities of calling the material to life; finding a way to confront and unite with the material, with one's own spiritual dynamics; combining human creative ability with the characteristics of the material; bringing the material to life; working with the material in a way that is completely appropriate to it; the artist serving the material - the artist's 'ego' is not or minimally visible (not giving one's work titles or provide interpretations) which allows for the material and the creative process to be the main elements in creation, the artist is secondary to that.; and finally embracing the beauty of the process, both the work process and the process of material and artistic ageing, of decay ultimately.

With this in mind I set about working with very wet clay - ideally it would have been the condition in which it comes from the quarry - manipulating, handling, moving the clay to let it take 'form'. The idea was to continue to do this until something 'interesting' (recognisable) happened - a movement, a plane, a concave.

Initially I threw small handfuls of clay onto a board. This produced 'smudges', all pretty similar. I then began taking larger handfuls and placed these less forcefully onto the board - reducing the intervention/impact from the artist - but still nothing much was really happening.

The next step was to saturate the clay with water to achieve a very loose but still holding consistency and I set about kneading it, moving it around, throwing it, dropping it from a height, swirling it, ... and here I felt I was beginning to really connect with the material. I had never 'felt' the clay as profoundly as that before, !in all the years I've worked with clay! I basked in the physicality of moving such a large mass around - physically quite demanding. The sound of the wet clay being moved by my hands. The texture, the smell, the sound, the physical resistance, the physical interaction ... what a joy!

The wetter the clay - of course - the more formless the clay and the more it obeys the laws of gravity - something else to work with.

I woke the following morning with the thought that my 'interference', my manipulating of the clay, should be kept to a minimum in order to let the clay live; let the clay do the creating and I simply initiate/facilitate - the artist serves the material.

I feel I need to point out that the initial intention was to use these wet-clay forms as 'foundation forms' from which to make 'a scultpure', and, as I recorded in my sketchbook, 'to find the interesting elements and use those as the basis for my form'. I saw them as 'the seed from which the sculpture would grow'. This dovetailed with my earlier exploration of what goes on underneath/behind [the positive/negative, which culminated in the piece entitled 'Abstract IV' as per my post of 30 March 2011]). I removed these 'interesting elements' and encased them in plaster. The discovery of the joy of exploring plaster as a material then took over, the evolution of which I shall describe in a subsequent post.

Ten months or so on, the evolution along the path of Gutai-inspired discovery has been such that I intend to revisit the wet-clay manipulations but retain them in their integrity. They will be the 'sculptures'.

Sunday, 23 September 2012

'These Associations' by Tino Seghal - Part II

Following on from my post of 3 August last of the same title:

I saw this piece again yesterday as I was at Tate Modern for the Tino Seghal Curator's Talk and this time I experienced it very differently. No conversation with a participant this time; I was viewing the unfolding from above up on the bridge. So the piece became about movement and fluidity of form, created by the group of participants. This is form/shapes created BY CHANCE through individuals moving around, seemingly randomly.

This new experiencing of the piece came about, I think, because I was watching from above and not from the level on which the participants were moving around, where the onlooker becomes more physically integrated into the piece and the only physical level on which the 'conversations' take place.

The movement element of the piece seemed and now seems more interesting to me than the conversation element as, over time, I have come to feel that these 'conversations' one has with the participants have a somewhat contrived feel and perhaps a triviality and unauthenticity about them. Interestingly, in the talk, the Producer Asad Raza said the opposite; that the conversations are authentic because there is no former knowledge of each other and it is therefore just the conversation, without the usual interference from prior knowledge/prejudice of occupational background, social status, nationality, etc.

Today, after yesterday's talk and viewings before and after the talk, I feel the fluidity of movement is the most interesting aspect: I was fascinated by the way the fluid movement of the group illustrated form and formlessness very nicely: the formation of the group is random at first and then begins to take form as you begin to see a pattern/structure develop and then dissipates again.

I suppose this is a good illustration of how this piece - and all art for that matter - is perceived by the viewer according to their own personal perspective; things resonate because you have a certain interest, you come from a certain background/culture.

Another interesting aspect, which I hadn't homed in on back in August, is the 'social' interaction between the participants. Perhaps it wasn't there so much in the early stages of the work and things have evolved, participants have begun to interact differently as they have become more familiar with their role, or the choreographic directions have changed. I enjoyed watching the participants watch each other, pairs homing in on each other and then from a distance begin to move around in a kind of almost synchronized series of movements. I feel this reflected real-life social interaction far more so than the 'conversations'.

Some of the notes I took during the talk:

Most people's subsequent comments in the social media and other platforms are about the conversations: 95%, to the surprise of the curator and producer. Why? Because they zoom in on the personal perspective, latching on to things that resonate with them at the time. My own personal view: also something to do with the physical position of the viewer (as commented on above).

Asad Arad: '20th century art is about defining what art is and then finding what it is not'.

This last comment gives much food for thought: if 20th century art was indeed about finding what art was not and if that has been explored to the full, what is 21st century art? It has to move on from the 20th century, therefore, as an artist in the 21st century I have to find a path through the labyrinth and find a place for myself that fits with who I am as an artist and a person. That requires some further thought ...

I saw this piece again yesterday as I was at Tate Modern for the Tino Seghal Curator's Talk and this time I experienced it very differently. No conversation with a participant this time; I was viewing the unfolding from above up on the bridge. So the piece became about movement and fluidity of form, created by the group of participants. This is form/shapes created BY CHANCE through individuals moving around, seemingly randomly.

This new experiencing of the piece came about, I think, because I was watching from above and not from the level on which the participants were moving around, where the onlooker becomes more physically integrated into the piece and the only physical level on which the 'conversations' take place.

The movement element of the piece seemed and now seems more interesting to me than the conversation element as, over time, I have come to feel that these 'conversations' one has with the participants have a somewhat contrived feel and perhaps a triviality and unauthenticity about them. Interestingly, in the talk, the Producer Asad Raza said the opposite; that the conversations are authentic because there is no former knowledge of each other and it is therefore just the conversation, without the usual interference from prior knowledge/prejudice of occupational background, social status, nationality, etc.

Today, after yesterday's talk and viewings before and after the talk, I feel the fluidity of movement is the most interesting aspect: I was fascinated by the way the fluid movement of the group illustrated form and formlessness very nicely: the formation of the group is random at first and then begins to take form as you begin to see a pattern/structure develop and then dissipates again.

I suppose this is a good illustration of how this piece - and all art for that matter - is perceived by the viewer according to their own personal perspective; things resonate because you have a certain interest, you come from a certain background/culture.

Another interesting aspect, which I hadn't homed in on back in August, is the 'social' interaction between the participants. Perhaps it wasn't there so much in the early stages of the work and things have evolved, participants have begun to interact differently as they have become more familiar with their role, or the choreographic directions have changed. I enjoyed watching the participants watch each other, pairs homing in on each other and then from a distance begin to move around in a kind of almost synchronized series of movements. I feel this reflected real-life social interaction far more so than the 'conversations'.

Some of the notes I took during the talk:

Most people's subsequent comments in the social media and other platforms are about the conversations: 95%, to the surprise of the curator and producer. Why? Because they zoom in on the personal perspective, latching on to things that resonate with them at the time. My own personal view: also something to do with the physical position of the viewer (as commented on above).

Asad Arad: '20th century art is about defining what art is and then finding what it is not'.

This last comment gives much food for thought: if 20th century art was indeed about finding what art was not and if that has been explored to the full, what is 21st century art? It has to move on from the 20th century, therefore, as an artist in the 21st century I have to find a path through the labyrinth and find a place for myself that fits with who I am as an artist and a person. That requires some further thought ...

Sunday, 26 August 2012

Notes from My Sketchbook - Gutai

Some of my immediate reflections on the Gutai manifesto, scribbled down in my sketchbook on Friday 15 September 2011 (see the post entitled 'Gutai - A Coming-Home' dated 21 August last for the full Gutai manifesto):

- Enjoy the materials you're using.

- Transcience of materials and artwork: use the material, photograph the outcome, destroy or let deteriorate.

- Gutai principle: intergrity of the material is all-important. Use materials so their properties are revealed/made the most of.

- Always, constantly, question what the material is about, and how can I demonstrate/reveal/show that?

- Make art to make art, not to exhibit and sell. Exhibiting/selling totally subsequent and main aim of exhibiting is to work with/alongside other, like-minded sculptors/artists.

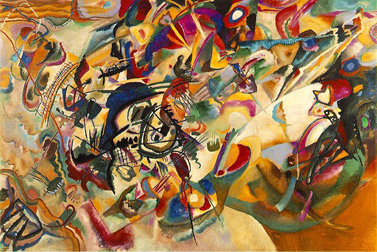

- What about the fundamental principle inherent in my work in the past - giving the viewer a moment of respite from hectic modern-day life? How can I keep to that whilst adopting/intergrating Gutai principles? cf. Theo van Doesburg: 'Art is a spiritual function of man, whith the purpose of delivering him from the chaos of life (tragedy).'

- How does marble carving fit into this?

- Direct responses to manifesto:

- !!'The human spirit and the material reach out their hands to each other'!! Beautiful!

- Materials loaded with false significance, not simply presenting their own material self but taking on the appearance of something else. Intellectual aim murders materials and they can no longer speak to us.

- Gutai art does not change the material; it brings it to life. Does not falsify the material. If you 'leave the material as it is', i.e. retain and reveal its integrity, it starts to speak/tell us something and does so with a mighty voice. Keeping the material alive also means bringing its spirit to life --> leads the material up to the height of the spirit.

- Disagree with art of the past not able to call up deep emotion in us: still contains and reveals the magnificent life and the spirit, albeit shrouded in a thick mist of subsequent intellectualism and affectation; can still evoke deep emotion, the problem is that these artworks can no longer be seen/viewed in a serene/peaceful way, away from the tourist hoards. Their age - decay in some - adds to that deep emotion. Important also to consider these artworks within their art-hsitorical context, not as art of today.

- Beauty of decay. I don't see it as the material 'taking revenge', simply the beauty of the process, i.e. the material continues to live after the artist has done his work, completed his stage in the process.

- Pollock et al. grapple with the material in a way that is completely appropriate to it. They serve the material. SERVE YOUR MATERIAL

to produce something living.

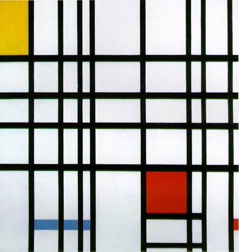

- Abstract Art - one of its merits: it has opened up the possibility to create a new subjective shape of space, one that truly deserves the name 'creation'.

- Combining human creative ability with the characteristics of the material.

- Kazuo Shiraga - spreading paint with his feet - had merely found a method that enabled him to confront and unite the material he had chosen with his own spiritual dynamics; no other motive.

- Constant message about the materials through characteristics, colours and form.

- ART - THE RESULT OF INVESTIGATING THE POSSIBILITIES OF CALLING THE MATERIAL TO LIFE.

- Enjoy the materials you're using.

- Transcience of materials and artwork: use the material, photograph the outcome, destroy or let deteriorate.

- Gutai principle: intergrity of the material is all-important. Use materials so their properties are revealed/made the most of.

- Always, constantly, question what the material is about, and how can I demonstrate/reveal/show that?

- Make art to make art, not to exhibit and sell. Exhibiting/selling totally subsequent and main aim of exhibiting is to work with/alongside other, like-minded sculptors/artists.

- What about the fundamental principle inherent in my work in the past - giving the viewer a moment of respite from hectic modern-day life? How can I keep to that whilst adopting/intergrating Gutai principles? cf. Theo van Doesburg: 'Art is a spiritual function of man, whith the purpose of delivering him from the chaos of life (tragedy).'

- How does marble carving fit into this?

- Direct responses to manifesto:

- !!'The human spirit and the material reach out their hands to each other'!! Beautiful!

- Materials loaded with false significance, not simply presenting their own material self but taking on the appearance of something else. Intellectual aim murders materials and they can no longer speak to us.

- Gutai art does not change the material; it brings it to life. Does not falsify the material. If you 'leave the material as it is', i.e. retain and reveal its integrity, it starts to speak/tell us something and does so with a mighty voice. Keeping the material alive also means bringing its spirit to life --> leads the material up to the height of the spirit.

- Disagree with art of the past not able to call up deep emotion in us: still contains and reveals the magnificent life and the spirit, albeit shrouded in a thick mist of subsequent intellectualism and affectation; can still evoke deep emotion, the problem is that these artworks can no longer be seen/viewed in a serene/peaceful way, away from the tourist hoards. Their age - decay in some - adds to that deep emotion. Important also to consider these artworks within their art-hsitorical context, not as art of today.

- Beauty of decay. I don't see it as the material 'taking revenge', simply the beauty of the process, i.e. the material continues to live after the artist has done his work, completed his stage in the process.

- Pollock et al. grapple with the material in a way that is completely appropriate to it. They serve the material. SERVE YOUR MATERIAL

to produce something living.

- Abstract Art - one of its merits: it has opened up the possibility to create a new subjective shape of space, one that truly deserves the name 'creation'.

- Combining human creative ability with the characteristics of the material.

- Kazuo Shiraga - spreading paint with his feet - had merely found a method that enabled him to confront and unite the material he had chosen with his own spiritual dynamics; no other motive.

- Constant message about the materials through characteristics, colours and form.

- ART - THE RESULT OF INVESTIGATING THE POSSIBILITIES OF CALLING THE MATERIAL TO LIFE.

Friday, 24 August 2012

Lee Ufan and Mono-ha

Another source of inspiration back in October last was the Mono-ha group.

Taken from the NMOA website - personal highlights in underscore as before:

http://www.nmao.go.jp

'Mono-ha was an important trend that should be viewed as a benchmark in Japanese postwar art history, and a movement that continues to raise a variety of questions.

"Mono-ha" was not a group assembled on the basis of a single doctrine or framework. Between 1968 and the early 1970s, the collection of artists who used "mono"(things), such as stone and wood, paper and cotton, and steel sheets and paraffin in their natural form, as either single substances or in combination with each other, came to be known as "Mono-ha." By presenting ordinary "things" just as they were in extraordinary circumstances, the artists were able to strip away preexisting concepts related to their materials and access a new world within them.

The huge conceptual shift that led to the emergence of this type of art is often traced to the 1st Exhibition of Contemporary Japanese Sculpture held at Kobe Suma Rikyu Park in October 1968, and the crucial role played by Sekine Nobuo's "Phase-Mother Earth," a work that contrasted a deep cylindrical hole in the earth with a cylindrical pile of dirt. Lee U fan, who had studied philosophy in Japan, suggested that "Phase-Mother Earth" contained a universal aspect which made an "encounter" with a "new world" possible, and thus provided a theoretical foundation for Mono-ha.

In light of increasingly accepted notions about what triggered the group's emergence, this exhibition attempts to reconsider "Mono-ha" in the context of the era by examining the many works and actions that were created by departing from conventional forms of expression in the search for a "new world." Among these are the artistic trend that originated with Takamatsu Jiro and others who dealt with the disparity between real and imaginary spaces, and contemporaneous attempts to explore the tense relationship between materials and human being.'

And some further insights into some of the Mono-ha artists:

http://www.tokyoartbeat.com/tablog/entries.en/2007/09/an-introduction-to-mono-ha.html

Taken from the NMOA website - personal highlights in underscore as before:

http://www.nmao.go.jp

'Mono-ha was an important trend that should be viewed as a benchmark in Japanese postwar art history, and a movement that continues to raise a variety of questions.

"Mono-ha" was not a group assembled on the basis of a single doctrine or framework. Between 1968 and the early 1970s, the collection of artists who used "mono"(things), such as stone and wood, paper and cotton, and steel sheets and paraffin in their natural form, as either single substances or in combination with each other, came to be known as "Mono-ha." By presenting ordinary "things" just as they were in extraordinary circumstances, the artists were able to strip away preexisting concepts related to their materials and access a new world within them.

The huge conceptual shift that led to the emergence of this type of art is often traced to the 1st Exhibition of Contemporary Japanese Sculpture held at Kobe Suma Rikyu Park in October 1968, and the crucial role played by Sekine Nobuo's "Phase-Mother Earth," a work that contrasted a deep cylindrical hole in the earth with a cylindrical pile of dirt. Lee U fan, who had studied philosophy in Japan, suggested that "Phase-Mother Earth" contained a universal aspect which made an "encounter" with a "new world" possible, and thus provided a theoretical foundation for Mono-ha.

In light of increasingly accepted notions about what triggered the group's emergence, this exhibition attempts to reconsider "Mono-ha" in the context of the era by examining the many works and actions that were created by departing from conventional forms of expression in the search for a "new world." Among these are the artistic trend that originated with Takamatsu Jiro and others who dealt with the disparity between real and imaginary spaces, and contemporaneous attempts to explore the tense relationship between materials and human being.'

And some further insights into some of the Mono-ha artists:

http://www.tokyoartbeat.com/tablog/entries.en/2007/09/an-introduction-to-mono-ha.html

Remember Lee Ufan?

In my post of 10 February this year I highlighted the work of Lee Ufan in order to raise - and aid understanding of - the question of chance playing an integral part in the making of an artwork (and to illustrate my own view on the issue).

This is him now:

And an explanation:

http://www.artcritical.com/2011/09/13/lee-ufan/

For Phenomena and Perception B, the artist recreated an iconic Mono-ha sculpture, dropping a boulder on a sheet of glass fitted to a steel plate. Originally Phenomena and Perception B read as a vigorous critique of Modernism’s query of personal identity, but, fifty years later, the work is a shattering indictment of virtuality. The physical world, Lee’s art suggests, reifies invisible forces and energies that exist in a constant negotiation of alliances—self and world, art and self, body and consciousness, ad infinitum. No wonder the sculptures derive their power from a fanatical obsession with equilibrium, in which various components—material, spatial and proportional—toggle between harmony and chaos. From the cosmic collision in Phenomena and Perception B to allusions to particle physics in his series From Point and From Line, discourse on the phenomena that give rise to empirical reality resonates throughout the show. In Relatum, (1978) in which a curved steel plate covers a perky stone in the way a heavy blanket covers a child, humanity seems to peek out from under (or through) existence, as if to playfully say, “here I am!”

The final room in the retrospective features an installation from the recent Dialogue series in which the ontological concerns of the paintings find their latest, and perhaps most powerful, iteration. On three of the gallery walls, Lee has placed a single square brush stroke from a six-inch brush loaded with oil paint and mineral pigment in a spectrum of luminescent grays, slates, and pearls. While for many years his palette favored a nearly Yves Klein blue, the artist now communicates in the elegant ambiguities of gray. The culminating work posits windows on reality that hover on the surface of the walls and simultaneously recede into the ground, so that the eye is drawn through and beyond the energized patches of paint into the “infinity” of the retrospective’s title. But losing oneself in the experience of these works is not an end in itself: viewers should leave the show convinced of their own existential worth.

This is him now:

And an explanation:

http://www.artcritical.com/2011/09/13/lee-ufan/

Encounters Between Seer and Seen: Lee Ufan at the Guggenheim

by Dawn-Michelle Baude

Lee Ufan: Marking Infinity at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

June 24–September 28, 2011

1071 Fifth Avenue (at 89th Street)

New York City 212-423-3500

Sensual the boulder upon the floor, sensual the metal plate against the wall. Sensual the water-glossed curves of stones, the muscular thickness of steel. The two components in Lee Ufan’s sculpture Relatum – silence B (2008)—the boulder sloping seductively toward the plate, the plate coyly leaning on the wall—flirt with each other and the viewer, who is drawn haplessly into a coquettish ménage-à-trois in the opening gallery of the artist’s first major exhibition on U.S. soil. Here, as elsewhere, the brute fact of materials– the industrial plate on the one hand and the geologic ready-made on the other– succumbs to a latent, often humorous, anthropomorphism or “encounter,” a term favored by the artist for the interface between seer and seen. To label the sculpture as Minimalist misses the point: it ignores the artist’s five decades of research into the notion of Art as a vehicle of altered consciousness in which the relationship between the audience and the artwork, between subject and object, is presented as a fragile, phenomenological nexus revelatory of Being.

Marking Infinity, Lee Ufan’s Guggenheim retrospective, is heady stuff. Perhaps the philosophical content of the work explains why it’s taken so long for the artist to be presented to America, whereas in the late 1960s, he was catapulted to fame in Asia as a founding member and critical proponent of the Japanese group Mono-ha (“School of Things”), committed to creating artworks from everyday materials—paper, rope, steel. In both his art and in his writing, the Korean-born Lee grew in stature in Asia over the decades, to the point that last year Japan celebrated the opening of the Lee Ufan Museum– a 32,000-square foot monument designed by none other than Japanese architect Tadao Ando. Lee’s delay in recognition from the West is particularly compelling, and perhaps even poignant, when contextualized within the artist’s lifelong commitment to the universality of art over, and against, Orientalism. For an artist whose work exalts the “encounter” (The Art of Encounter is the key collection of Lee’s translated writings) and the “relationship” (nearly all his sculptures are entitled Relatum), the fragmenting tendencies of identity politics and otherness run counter to the inclusive purview of Being.1071 Fifth Avenue (at 89th Street)

New York City 212-423-3500

Installation view of Lee Ufan: Marking Infinity, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, June 24–September 28, 2011 Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, showing (left) Relatum—silence b, 2008, courtesy The Pace Gallery, New York, and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, and (right) Dialogue, 2007, Ovitz Family Collection, Los Angeles

Lee Ufan breaking the glass for Relatum (formerly Phenomena and Perception B), 1968/2011, during installation of Lee Ufan: Marking Infinity at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, June 2011 Photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

For Phenomena and Perception B, the artist recreated an iconic Mono-ha sculpture, dropping a boulder on a sheet of glass fitted to a steel plate. Originally Phenomena and Perception B read as a vigorous critique of Modernism’s query of personal identity, but, fifty years later, the work is a shattering indictment of virtuality. The physical world, Lee’s art suggests, reifies invisible forces and energies that exist in a constant negotiation of alliances—self and world, art and self, body and consciousness, ad infinitum. No wonder the sculptures derive their power from a fanatical obsession with equilibrium, in which various components—material, spatial and proportional—toggle between harmony and chaos. From the cosmic collision in Phenomena and Perception B to allusions to particle physics in his series From Point and From Line, discourse on the phenomena that give rise to empirical reality resonates throughout the show. In Relatum, (1978) in which a curved steel plate covers a perky stone in the way a heavy blanket covers a child, humanity seems to peek out from under (or through) existence, as if to playfully say, “here I am!”

The final room in the retrospective features an installation from the recent Dialogue series in which the ontological concerns of the paintings find their latest, and perhaps most powerful, iteration. On three of the gallery walls, Lee has placed a single square brush stroke from a six-inch brush loaded with oil paint and mineral pigment in a spectrum of luminescent grays, slates, and pearls. While for many years his palette favored a nearly Yves Klein blue, the artist now communicates in the elegant ambiguities of gray. The culminating work posits windows on reality that hover on the surface of the walls and simultaneously recede into the ground, so that the eye is drawn through and beyond the energized patches of paint into the “infinity” of the retrospective’s title. But losing oneself in the experience of these works is not an end in itself: viewers should leave the show convinced of their own existential worth.

Tuesday, 21 August 2012

Gutai - Continued

A further, concise insight into the Gutai movement; truly ground-breaking artists, considering the group formed in 1954:

http://www.nipponlugano.ch/en/gutai-multimedia/narrazione/project/narrazione_page-1_nav-short.html

This website emphasizes the group's interest in what they called 'painting actions' - as opposed to the 'action paintings' of the likes of Pollock (the painting functioning as a record of his movements and gestures) and others.

http://www.nipponlugano.ch/en/gutai-multimedia/narrazione/project/narrazione_page-1_nav-short.html

This website emphasizes the group's interest in what they called 'painting actions' - as opposed to the 'action paintings' of the likes of Pollock (the painting functioning as a record of his movements and gestures) and others.

Gutai - A Coming-Home

I first came across the Gutai manifesto back in September last year. It was like a coming-home; one of those life changing moments, following a spring and summer of repeated and ever-deepening disenchantment with the art world - the state of the 'exhibition' or 'art show' as an institution; the phenomenon of the 'Private View' (which epitomizes the predicament in which the art world currently finds itself); the raison d'être of the gallerist, curator, and collector; buyers' and the public's expectations, etc. (my glum outlook has lifted somewhat since then) - and with some of my choices and uses of materials. This manifesto put into words the things I had been feeling and thinking for some time - highlighted in underscore:

'With our present-day awareness, the arts as we have known them up to now appear to us in general to be fakes fitted out with a tremendous affectation. Let us take leave of these piles of counterfeit objects on the altars, in the palaces, in the salons and the antique shops.

They are an illusion with which, by human hand and by way of fraud, materials such as paint, pieces of cloth, metals, clay or marble are loaded with false significance, so that, instead of just presenting their own material, they take on the appearance of something else. Under the cloak of an intellectual aim, the materials have been completely murdered and can no longer speak to us.

Lock these corpses into their tombs. Gutai art does not change the material but brings it to life. Gutai art does not falsify the material. In Gutai art the human spirit and the material reach out their hands to each other, even though they are otherwise opposed to each other. The material is not absorbed by the spirit. The spirit does not force the material into submission. If one leaves the material as it is, presenting it just as material, then it starts to tell us something and speaks with a mighty voice. Keeping the life of the material alive also means bringing the spirit alive. And lifting up the spirit means leading the material up to the height of the spirit.

Art is the home of the creative spirit, but never until now has the spirit created matter. The spirit has only ever created the spiritual. Certainly the spirit has always filled art with life, but this life will finally die as the times change. For all the magnificent life which existed in the art of the Renaissance, little more than its archaeological existence can be seen today.

What is still left of that vitality, even if passive, may in fact be found in Primitive Art or in art since Impressionism. These are either such things in which, due to skillful application of the paint, the deception of the material had not quite succeeded, or else those like Pointillist or Fauvist pictures in which the materials, although used to reproduce nature, could not be murdered after all. Today, however, they are no longer able to call up deep emotion in us. They already belong to a world of the past.

Yet what is interesting in this respect is the novel beauty which is to be found in works of art and architecture of the past even if, in the course of the centuries, they have changed their appearance due to the damage of time or destruction by disasters. This is described as the beauty of decay, but is it not perhaps that beauty which material assumes when it is freed of artificial make-up and reveals its original characteristics? The fact that the ruins receive us warmly and kindly after all, and that they attract us with their cracks and flaking surfaces, could this not really be a sign of the material taking revenge, having recaptured its original life? In this sense I pay respect to [Jackson] Pollock's and [Georges] Mathieu's works in contemporary art. These works are the loud outcry of the material, of the very oil or enamel paints themselves. These two artists grapple with the material in a way which is completely appropriate to it and which they have discovered due to their talent. This even gives the impression that they serve the material. Differentiation and integration create mysterious effects.

Recently, Tominaga So'ichi and Domoto Hisao presented the activities of Mathieu and [Michel]Tapié in informal art, which I found most interesting. I do not know all the details, but in the content presented, there were many points I could agree with. To my surprise, I also discovered that they demanded the immediate revelation of anything arising spontaneously and that they are not bound by the previously predominant forms. Despite the differences in expression as compared to our own, we still find a peculiar agreement with our claim to produce something living. If one follows this possiblity, I am not sure as to the relationship in which the conceptually defined pictorial elements like colours, lines, shapes, in abstract art are seen with regard to the true properties of the material. As far as the denial of abstraction is concerned, the essence of their declaration was not clear to me. In any case, it is obvious to us that purely formalistic abstract art has lost its charm and it is a fact that the foundation of the Gutai Art Society three years ago was accompanied by the slogan that they would go beyond the borders of Abstract Art and that the name Gutaiism (Concretism) was chosen. Above all we were not able to avoid the idea that, in contrast to the centripetal origin of abstraction, we of necessity had to search for a centrifugal approach.

In those days we thought, and indeed still do think today, that the most important merits of Abstract Art lie in the fact that it has opened up the possibility to create a new, subjective shape of space, one which really deserves the name creation.

We have decided to pursue the possibilities of pure and creative activity with great energy. We thought at that time, with regard to the actual application of the abstract spatial arts, of combining human creative ability with the characteristics of the material. When in the melting-pot of psychic automatism the abilities of the individual united with the chosen material , we were overwhelmed by the shape of space still unknown to us, never before seen or experienced. Automatism, of necessity, reaches beyond the artist's self. We have struggled to find our own method of creating a space rather than relying on our own self. The work of one of our members will serve as an example. Yoshiko Kinoshita is actually a teacher of chemistry at a girls' school. She created a peculiar space by allowing chemicals to react on filter paper. Although it is possible to imagine the results beforehand to a certain extent, the final results of handling the chemicals cannot be established until the following day. The particular results and the shape of the material are in any case her own work. After Pollock many Pollock-imitators appeared, but Pollock's splendour will never be extinguished. The talent of invention deserves respect.

Kazuo Shiraga placed a lump of paint on a huge piece of paper, and started to spread it around violently with his feet. For about the last two years art journalists have called this unprecedented method "the Art of committing the whole self with the body." Kazuo Shiraga had no intention at all of making this strange method of creating a work of art public. He had merely found a method which enabled him to confront and unite the material he had chosen with his own spiritual dynamics. In doing so he achieved an extremely convincing result.

In contrast to Shiraga, who works with an organic method, Shōzō Shimamoto has been working with mechanical manipulations for the past few years. The pictures of flying spray created by smashing a bottle full of paint, or the large surface he creates in a single moment by firing a small, hand-made cannon filled with paint by means of an acetylene gas explosion, etc., display a breathtaking freshness.

Other works which deserve mention are those of Yasuo Sumi produced with a concrete mixer, or Toshio Yoshida, who uses only one single lump of paint. All their actions are full of a new intellectual energy which demands our respect and recognition.

The search for an original, undiscovered world also resulted in numerous works in the so-called object form. In my opinion, conditions at the annual open-air exhibitions in the city of Ashiya have contributed to this. The way in which these works, created by artists who are confronted with many different materials, differ from the objects of Surrealism can be seen simply from the fact that the artists tend not to give them titles or to provide interpretations. The objects in Gutai art were, for example, a painted, bent iron plate (Atsuko Tanaka) or a work in hard red vinyl in the form of a mosquito net (Tsuruko Yamazaki), etc. With their characteristics, colours and forms, they were constant messages about the materials.

Our group does not impose restrictions on the art of its members, providing they remain in the field of free artistic creativity. For instance, many different experiments were carried out with extraordinary activity. This ranged from an art to be felt with the entire body to an art which could only be touched, right through to Gutai music (in which Shōzō Shimamoto has been doing interesting experiments for several years). There is also work by Shōzō Shimamoto like a horizontal ladder with bars which you can feel as you walk over them. Then a work by Saburo Murakami which is like a telescope you can walk into and look up at the heavens, or an installation made of plastic bags with organic elasticity, etc. Atsuko Tanaka started with a work of flashing light bulbs which she called "Clothing." Sadamasa Motonaga worked with water, smoke, etc. Gutai art attaches the greatest importance to all daring steps which lead to an as yet undiscovered world. Sometimes, at first glance, we are compared with and mistaken for Dadaism, and we ourselves fully recognize the achievements of Dadaism, but we do believe that, in contrast to Dadaism, our work is the result of investigating the possibilities of calling the material to life.

We shall hope that a fresh spirit will always blow at our Gutai exhibitions and that the discovery of new life will call forth a tremendous scream in the material itself.

(Proclaimed in October 1956)

Jirō YOSHIHARA

'With our present-day awareness, the arts as we have known them up to now appear to us in general to be fakes fitted out with a tremendous affectation. Let us take leave of these piles of counterfeit objects on the altars, in the palaces, in the salons and the antique shops.

They are an illusion with which, by human hand and by way of fraud, materials such as paint, pieces of cloth, metals, clay or marble are loaded with false significance, so that, instead of just presenting their own material, they take on the appearance of something else. Under the cloak of an intellectual aim, the materials have been completely murdered and can no longer speak to us.

Lock these corpses into their tombs. Gutai art does not change the material but brings it to life. Gutai art does not falsify the material. In Gutai art the human spirit and the material reach out their hands to each other, even though they are otherwise opposed to each other. The material is not absorbed by the spirit. The spirit does not force the material into submission. If one leaves the material as it is, presenting it just as material, then it starts to tell us something and speaks with a mighty voice. Keeping the life of the material alive also means bringing the spirit alive. And lifting up the spirit means leading the material up to the height of the spirit.

Art is the home of the creative spirit, but never until now has the spirit created matter. The spirit has only ever created the spiritual. Certainly the spirit has always filled art with life, but this life will finally die as the times change. For all the magnificent life which existed in the art of the Renaissance, little more than its archaeological existence can be seen today.

What is still left of that vitality, even if passive, may in fact be found in Primitive Art or in art since Impressionism. These are either such things in which, due to skillful application of the paint, the deception of the material had not quite succeeded, or else those like Pointillist or Fauvist pictures in which the materials, although used to reproduce nature, could not be murdered after all. Today, however, they are no longer able to call up deep emotion in us. They already belong to a world of the past.

Yet what is interesting in this respect is the novel beauty which is to be found in works of art and architecture of the past even if, in the course of the centuries, they have changed their appearance due to the damage of time or destruction by disasters. This is described as the beauty of decay, but is it not perhaps that beauty which material assumes when it is freed of artificial make-up and reveals its original characteristics? The fact that the ruins receive us warmly and kindly after all, and that they attract us with their cracks and flaking surfaces, could this not really be a sign of the material taking revenge, having recaptured its original life? In this sense I pay respect to [Jackson] Pollock's and [Georges] Mathieu's works in contemporary art. These works are the loud outcry of the material, of the very oil or enamel paints themselves. These two artists grapple with the material in a way which is completely appropriate to it and which they have discovered due to their talent. This even gives the impression that they serve the material. Differentiation and integration create mysterious effects.